Home sweet home: Automating novel object recognition

Novel object recognition (NOR) is a staple behavioural test in rodent memory research. The principle is simple: animals naturally explore new objects more than familiar ones. By measuring this preference, researchers can study different aspects of memory, and the test is especially relevant for Alzheimer’s disease research. In practice, however, NOR tests are highly sensitive to experimental variability. Factors such as arena design, handling, lighting, temperature, humidity, time of day, seasonality, how “exploration” is defined, experimenter, and even subtle differences between objects can all influence the results.

A new study, led by researchers at the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL, the University of Cambridge and the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre at UCL, tackles these challenges. Published today in Cell Reports Methods, the team have developed and validated a fully automated NOR test that runs entirely in a mouse’s home cage. By removing many sources of variability, the setup allows for more reliable measurements of memory, including long-term retention. The findings were consistent across different facilities.

“Our approach largely eliminates human biases and environmental inconsistencies in the novel object recognition test,” says Loukia Katsouri, Senior Research Associate in the O’Keefe Lab at SWC. “The setup improves welfare and standardisation, and it captures more naturalistic behaviour. Our goal is to use this test to measure memory deficits in mice with features of Alzheimer’s disease.”

“For neuroscientists studying memory, neurodegeneration, or cognitive enhancers, this home-cage-based novel object recognition system offers a reliable and scalable tool to investigate both short- and long-term memory,” adds Julija Krupic, Group Leader, UK Dementia Research Centre at UCL and lead author of the study.

The researchers hope the setup can be easily adopted by other labs, with confidence that results will be comparable. It could also be a new way to study changes in memory and neurodegeneration, and to test ways of improving memory performance.

Assessing object recognition

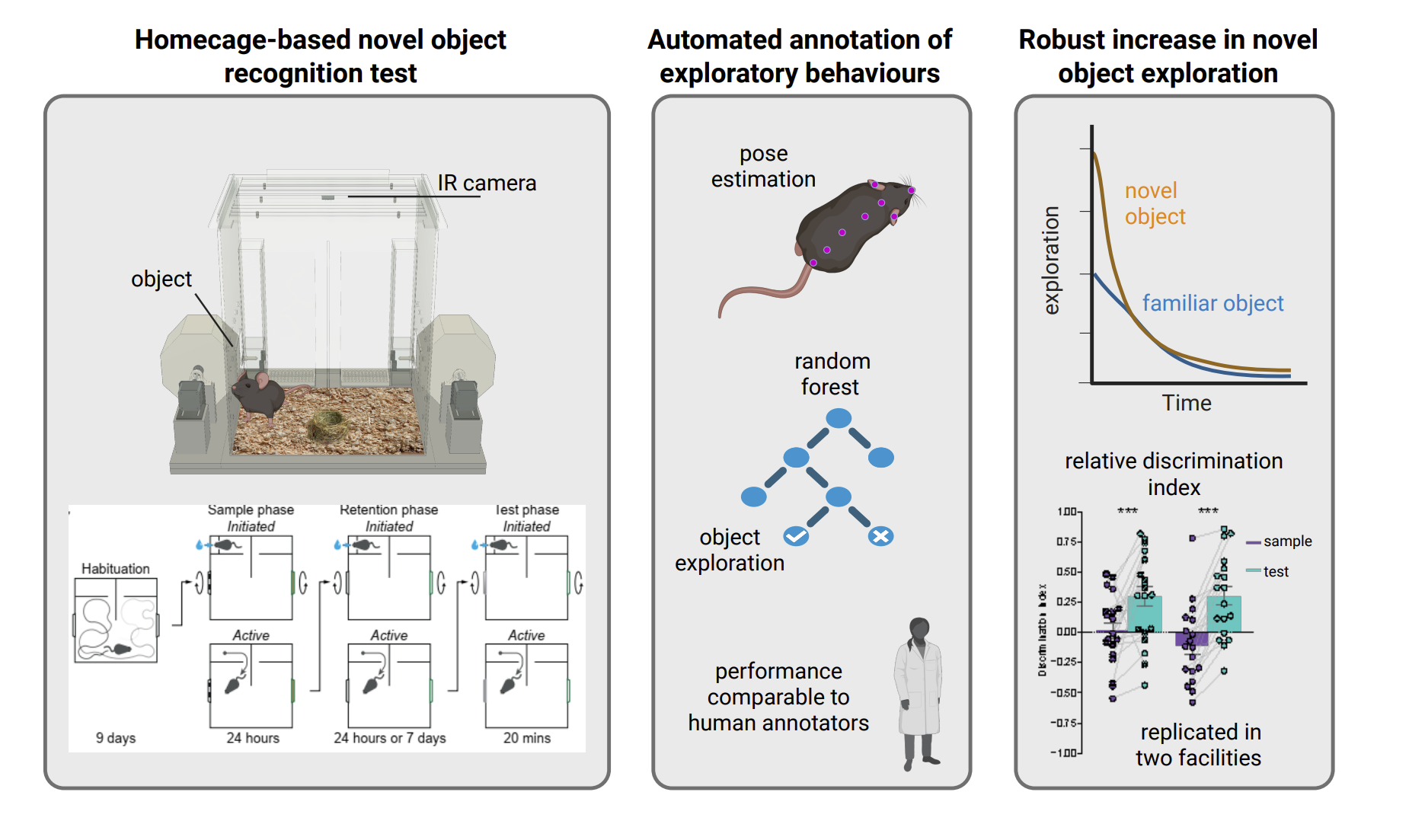

Unlike traditional NOR tests, which require moving animals between an arena and their home cage during the different phases of the task, potentially causing stress, the new design was conducted entirely within the animals’ home cages without any human intervention. While the setups differed slightly between the two facilities in the study, both used smart-Kages featuring continuous video monitoring, stable and controlled conditions, enrichment, and fully automated food and water delivery.

Smart-Kage, Cambridge Phenotyping. Credit: Krupic Lab, UKDRI.

The mice had a baseline pattern displayed in their home cage from the beginning of their habituation (similar to wallpaper or a painting in a room). After nine days of habituation, sampling objects were introduced while the animals were drinking at the waterspout and not looking, to avoid any positional bias. Most of the mice engaged immediately with the objects. Twenty-four hours later, the objects returned to the baseline pattern - their familiar “wallpaper.” After a predetermined period of either 24 hours or 7 days, the objects were changed to include a novel pattern that the mice had never encountered before (the novel object) and an identical one to one of the two objects they had previously explored (the familiar object). In both facilities, the mice consistently preferred the novel objects over the familiar ones. This preference persisted after 24 hours and 7 days, indicating that the test can be used to assess long-term object memory. Interestingly, the mice demonstrated object recognition from a distance, an observation that standard testing methods, which usually assess interaction in a small arena, do not allow.

Another strength of the approach is the use of automated behavioural analysis. Rather than relying on manual scoring of object exploration, which is time-consuming and subjective, the team developed machine learning classifiers to track animals and identify exploratory behaviour.

To validate the classifiers, their performance was compared against annotations from four human scorers: three independent experts and one completely naïve assessor. Agreement between the classifier and all human annotators was high.

Graphic illustration of the study. Panel one shows the smart-Kage, and a schematic of the different phases of the task. Panel two shows automated annotation of exploratory behaviours. Panel three shows the increase in novel object exploration.

Implications for translational research

The researchers hope that the test can be used in any laboratory with confidence that the results are comparable. They aim to assess the setup further, to find out if it could serve as a pharmacodynamic readout, allowing them to spot subtle differences in memory performance and to see whether new treatments can restore function.

Watch Dr Julija Krupic and Dr Marius Bauza discuss smart Kages.