Under pressure: Does everyday stress affect financial decisions?

Many of the negative effects of prolonged stress are well-known. In the brain, chronic stress reduces our ability to think. It makes solving problems, as well as regulating our behaviour, harder. This, in turn, can lead to more stress.

But when it comes to the effects of stress on making decisions, especially choices that pit instant gratification against delayed reward, the picture is less clear. Research so far has produced mixed results, and most studies have examined acute, not chronic stress.

To close that gap, Dr Jeffrey Erlich, Group Leader at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre, and Dr Evgeniya Lukinova, Assistant Professor at the University of Nottingham, studied the levels of stress in participants as they made financial decisions in laboratory tests. Participants were paid based on the outcomes: the more they were willing to wait, the bigger the payment was likely to be.

Dr Jeffrey Erlich said, “Discounting the future consequences of financial decisions can be harmful – it might result in gambling, impulse buying, or not having insurance. Our hypothesis was that chronic stress, like the kind of stress that might be caused by poverty, would increase that discounting. Our latest data supports this idea, though the picture is complex.”

The work, published today in Frontiers in Psychology and conducted at NYU Shanghai, found that certain cortisol measures correlated with a reduced willingness to wait – but only when the participant had to sit and actually experience the waiting.

The delayed discounting task

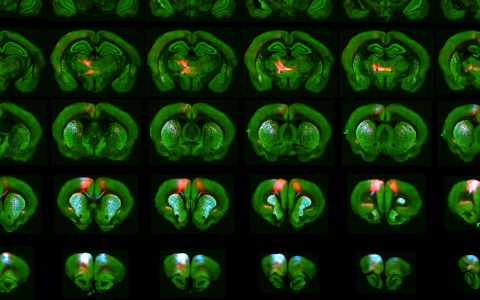

The work builds on the team’s previous research, where they developed a ‘delayed discounting task’ for humans. The task is based on the design of similar tasks for rodents, meaning that results can be compared between species.

Fourty-one adults took part in the new study, with payment tied to how they performed. In each trial, participants choose between two options: coins delivered instantly, or coins delivered after a delay of seconds, days or weeks. In each case, greater rewards are more likely if people wait or postpone. At the end, the total number of coins collected is converted to payment in local currency.

Participants took part in the delayed discounting task on multiple separate occasions, on average two weeks apart. The team hypothesised that if a person’s stress increased between sessions, they would be more likely to make impulsive decisions.

Measuring stress

The researchers assessed stress using questionnaires and by measuring cortisol levels in both saliva and hair samples. Cortisol levels are notoriously messy to interpret; exercise, time of day and what you eat all have an effect. Because one centimetre (cm) of hair represents a month of growth, analysing levels of cortisol in a one-centimetre segment provided a clearer picture of the level of the hormone over a longer period.

“Because we took repeated measurements of cortisol over time from each person, we were able to compare one task session to the next – this is a really important part of the study design,” says Dr Erlich. “I hope it influences future work.”

Within individuals, measures of cortisol in hair correlated with the reduction in willingness to wait in the task, but only when the wait was in seconds.

“This can be thought of as active waiting,” explained Dr Erlich. “Like waiting for a bus – you are experiencing that delay. Minigames on our phones – where you can either wait five minutes or pay to level up, tap into this. This is a very different experience from waiting for your retirement savings to mature. You don’t actively wait and think about that.”

For tasks with longer delays of days or weeks, the team didn’t find an association between cortisol and choosing the delayed option. This could be because the effect of stress on this kind of decision is weaker, and so would need a larger study with more participants to be able to detect it.

“Overall, cortisol levels explained roughly 10% of the differences in how strongly people discounted future rewards. Stress isn’t the whole story, but it plays a noticeable role,” says Dr Erlich.

The neurobiology of economic decision-making

Time preferences – the trade-offs people make between receiving a larger reward later or a smaller reward sooner - have been found to predict a wide range of life outcomes, including academic achievement, income, antisocial behaviour, drug-use and more

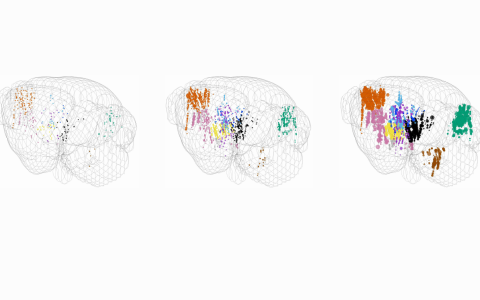

The Erlich Lab’s current focus is on breaking down decision-making into component parts, with particular interest in how learning rates affect the tolerance of risk.

Learning shapes economic behaviour in powerful ways. If you learn too quickly from a bad outcome, for example failing to win the lottery, you might avoid similar choices in the future. For the lottery, that’s helpful, because you’re never going to win. But in a game with 50/50 odds, overreacting to a single loss can lead to poor decisions. The context matters.

Relative amounts of money are also important. For someone who is struggling to cover their bills, losing £50 in a coin toss could be devastating. For a wealthy individual, the same loss might feel trivial, like the price of a casual dinner.

“It is not yet understood how ongoing, background stress levels – caused by financial instability, relationship strain, or health concerns - shape economic preferences over time. Our work suggests that stress does play a role in impulsivity. It is important to understand all the different aspects of decision-making – this knowledge can inform the design of systems, regulations and policies,” says Dr Erlich.

Find out more

Erlich Lab https://www.sainsburywellcome.org/web/groups/erlich-lab