Have we misunderstood fear and anxiety?

An interview with Professor Joseph E LeDoux conducted by April Cashin-Garbutt, MA (Cantab)

Have we misunderstood fear and anxiety? This was the question Professor Joseph E LeDoux, New York University and Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, posed in a recent seminar at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre. I caught up with him to find out more about his research and what other areas of neuroscience can learn from this conceptual reframing of fear.

What have been the main barriers in the translation of laboratory research on fear into treatments?

Part of the problem is conceptual: fields develop on the basis of findings, which are then interpreted. As scientists, and particularly psychologists, we’re interested in the mind because of our own experiences. We do experiments and create behavioural tests, strategies and paradigms that will allow us to translate our introspective experiences from our own life into things we find interesting that we might be able to study through laboratory research.

When we do this in animals, we’re taking some of the highest capacities of the human brain, such as the ability to introspect about our experiences and emotions, and use these to try and figure out what’s going on in the brain and we interpret the brain’s control over behaviour in terms of these complex experiences.

For example, I’ve studied the part of the brain called the amygdala for a long time. This brain area is known to detect threats and control behavioural responses to defend against the potential harm. Many researchers say that this tells where fear lives in the brain. The amygdala has in fact come to be known as a fear centre.

Stepping back and thinking about this logically, is it reasonable to expect that the highest capacities of the human brain can introspect into what a deep structure, such as the amygdala, is doing, or are we looking at something else when we study the amygdala? Maybe we’re projecting our subjective experiences onto that part of the brain, since when we we’re in danger, we both feel fear and we also freeze or flee. But maybe we’re simply the ability of the brain to detect and respond to threats.

So we are committing the sin that all scientists are taught never to make: confusing correlation with causation. In our minds, our defensive responses are correlated with our subjective experiences. But it turns out that the correlation is not as strong scientifically as it is subjectively.

We are all subject to confirmation bias. For example, we have a certain expectation that when we’re afraid we will freeze or flee. So we ignore the fact that sometimes we’re not freezing or fleeing when we’re afraid. Furthermore, when we see someone else freezing or fleeing, we assume that they are fearful, but there are lots of instances where people are very calm and collected and appear to make rational decisions in a situation of danger.

So we tend to assume that if a rat or mouse is freezing or fleeing it is afraid. It is very hard to avoid such anthropomorphic assumptions, but as scientists we have an obligation to do so. We spend so much effort being precise in our data collection and our experimental design, and we need to be just as precise when we interpret the data. I think we have been a little lax in how we have attributed the subjective states to behaviour. And a big part of the problem is that we use subjective state names and labels for non-subjective behavioural control circuits.

What do you think the future holds for treating problems related to fear and anxiety?

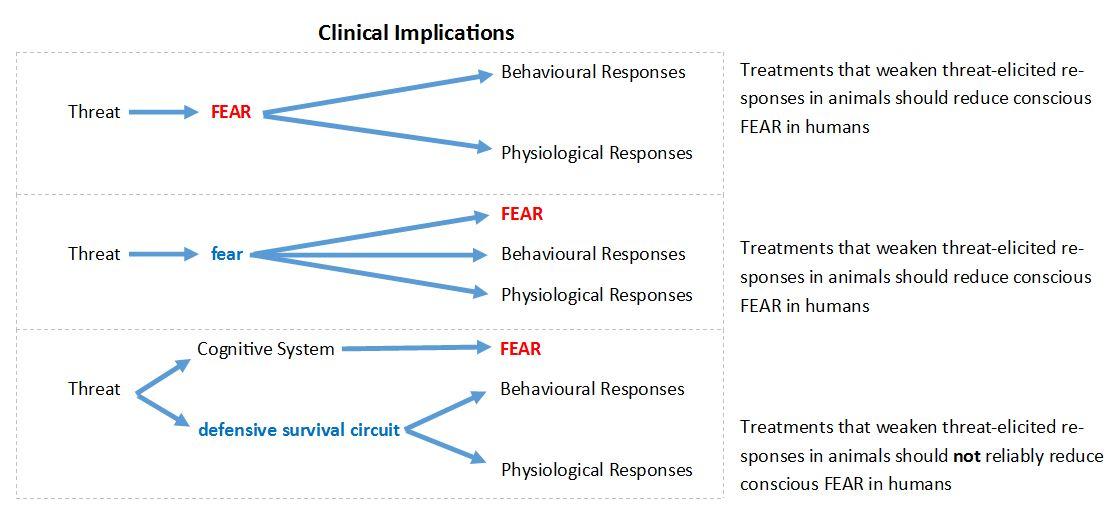

The problem is the way we develop treatments and medicines. We put animals through challenging situations and we measure their behaviour. If the animal is less responsive to threats when taking the drug, we assume it is because it is less fearful, as the drug must have changed the state of fear and therefore changed the animal’s behaviour.

Thus we think when we give this drug to people, they should be less fearful. However, what one sees, for example, is that a person with social anxiety may find it easier to go to the party, but may still feel anxious while they are there.

Now imagine this person is given two different talks by a therapist before receiving the drug. Therapist one says, you are going to take this drug and it will take a few weeks to kick-in, but once it does, you’ll be able to go to the party and you won’t feel anxious.

The second psychiatrist says, once the drug kicks-in you will find it easier to go to the party but you are still going to feel a little bit anxious while you are there but you can regulate your tolerance by stepping in and out and use this to develop your skills. The medication will help you have a social life in these kinds of situations. It may not be perfect but with time and patience you can use this to work your way in and make friends.

In the second scenario the person has the proper expectations about what the drug can do. In the first scenario the person doesn’t so they become disappointed. Consequently, the therapist is disappointed and the drug company is disappointed.

Many of the big companies are getting out of the anti-anxiety business as they say it has failed. But it hasn’t failed, they just had the wrong expectation. For example in 2010, Andrew Witty, the CEO of GlaxoSmithKline, said that they are done as there is no chance of success and they are not making money. If they stuck closer to the data they would have concluded that the drug would reduce behavioral timidity. And then everyone would have been on the same page and the drug would be viewed as successful.

In what ways are animal findings on fear limited?

Animal findings are limited because all we can do is measure their behavioural and physiological responses. This is important because some patients need help regulating pathological avoidance behaviour and physiological hyper-arousal.

Medications developed in animals can both ease the entry into the threatening situation and also reduce the arousal you have when they are there.

Again this is about what we’re expecting the medication to do. If we understand what the medication does, everyone will be better off.

Animal research is very important but we water down its importance when we promote the wrong expectations about it. It is important to have as much rigour in our interpretation as in our data collection.

Why do you think we have misunderstood what fear is?

We’ve called all this behavioural and physiological stuff fear and once you do that you create the expectation that fear, the feeling of being afraid, is what you are going to change with the medication.

How did this all come to pass? The behaviourists got rid of subjective states but not of subjective state terms, so fear became a kind of behavioural response: a tendency to behave in the presence of a danger.

So when researchers started studying the brain in relation to these behavioural techniques, the brain circuits that controlled the behaviour became fear circuits.

If so, a change in the fear circuits should change the fear experience. But it is not a fear circuit and the medications only change the behaviour. So I think we need to be more precise when we use the term fear. Let’s call a spade a spade, let subjective state terms refer to subjective states. This should get rid of the confusion.

Up until now many therapists have felt like they had to put subjective experiences on the back-burner as science wasn’t saying subjective experience is too soft, but now we’re in an age of great progress in cognitive science studies of perceptual consciousness. I think we can build on that to study emotional consciousness as well and I think that bringing subjective experience back to therapy and the study of emotions is an important thing.

What can other areas of neuroscience learn from this conceptual reframing?

My focus is on fear and emotion but I think this is true of many areas, including reward research, could benefit from soul-searching. This work started out as being about reinforcement and how to change behaviour by its consequences. But reinforcement, became reward, and then reward became pleasure.

Now whenever we talk about reward, the natural inclination is to think of it as pleasure. It is true that food may be pleasurable to eat, but pleasure is not necessarily the reason we go back to the restaurant. We learn behavioural tendencies through reinforcement, regardless of whether we experience pleasure.

For example, in drug addiction, the addiction is not about the pleasure. You may experience pleasure, which may cause you to take the drug again initially, but once you’ve taken it a few times, you are no longer motivated by pleasure as another system has taken over. The pleasure is gone and the habit system is now driving your behaviour.

About Professor Joseph E LeDoux

Joseph LeDoux is the Henry and Lucy Moses Professor of Science at NYU in the Center for Neural Science, and he directs the Emotional Brain Institute of NYU and the Nathan Kline Institute. He also a Professor of Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical School.

His work is focused on the brain mechanisms of memory and emotion and he is the author of The Emotional Brain, Synaptic Self, and Anxious. LeDoux has received a number of awards, including William James Award from the Association for Psychological Science, the Karl Spencer Lashley Award from the American Philosophical Society, the Fyssen International Prize in Cognitive Science, Jean Louis Signoret Prize of the IPSEN Foundation, the Santiago Grisolia Prize, the American Psychological Association Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award, and the American Psychological Association Donald O. Hebb Award. His book Anxious received the 2016 William James Book Award from the American Psychological Association.

LeDoux is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the New York Academy of Sciences, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and a member of the National Academy of Sciences. He is also the lead singer and songwriter in the rock band, The Amygdaloids and performs with Colin Dempsey as the acoustic duo So We Are.