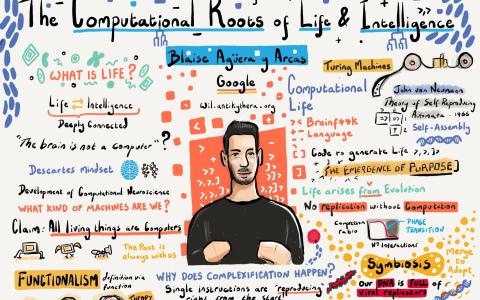

Understanding crowd behaviour: have we learned from Covid-19?

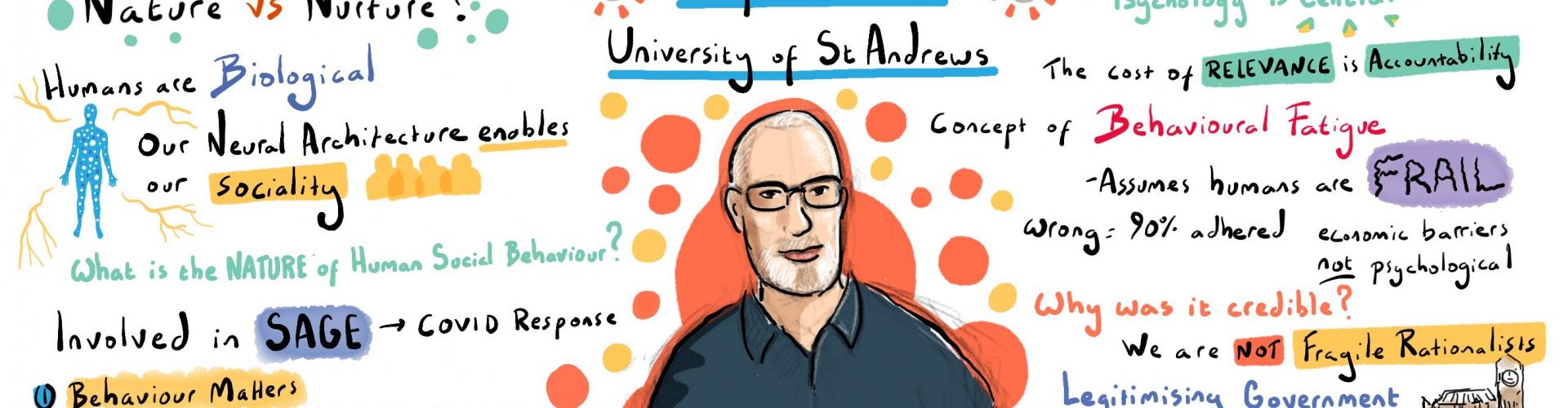

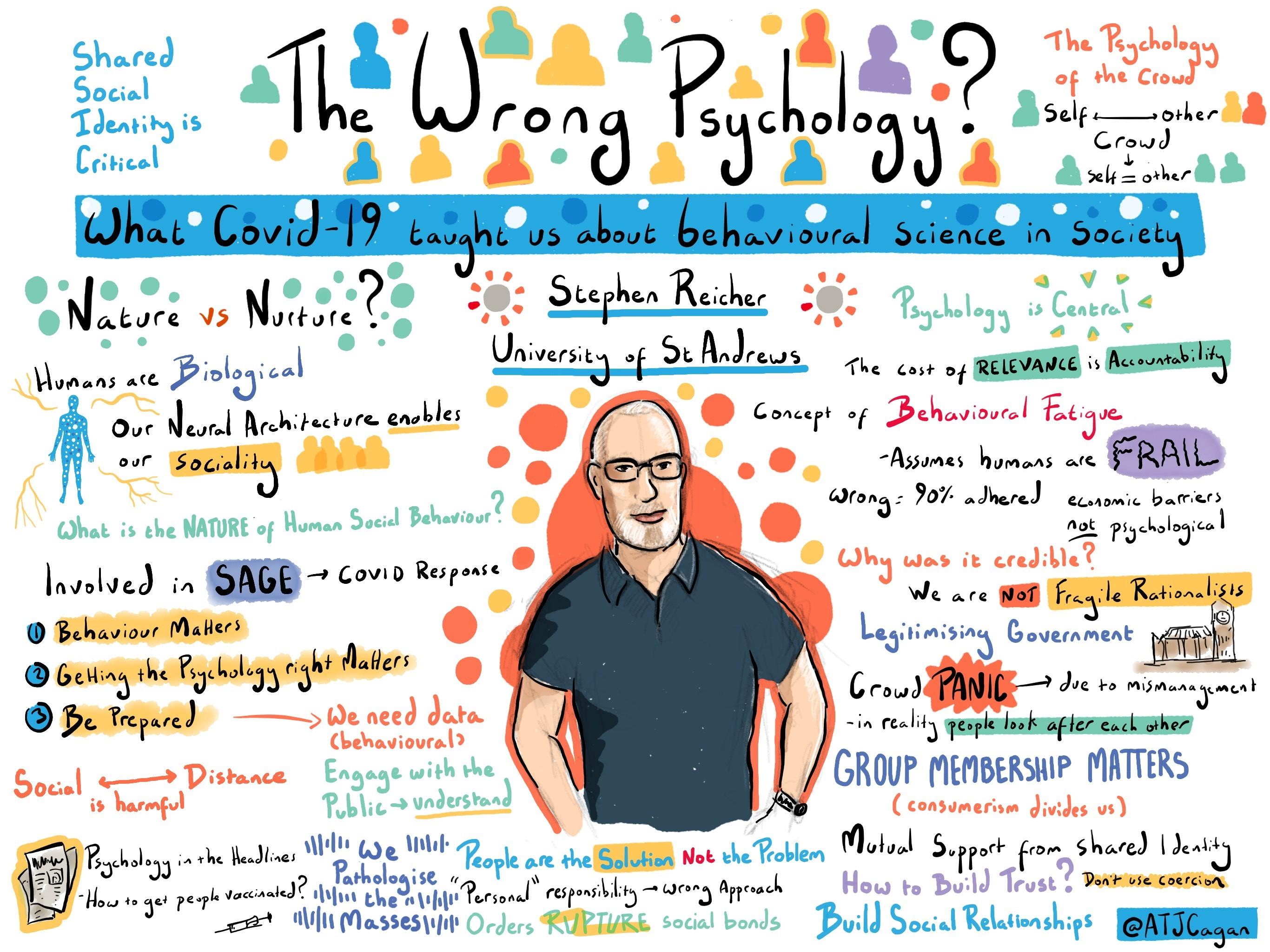

An interview with Professor Stephen Reicher, University of St Andrews, conducted by April Cashin-Garbutt

“One of the most stupid debates in psychology, is the nature-nurture debate,” Professor Stephen Reicher said as he opened the 2023 SWC Lecture. He explained how humans are irreducibly biological and our neural architecture allows us to be social beings. But, equally, we are irreducibly social and our variability according to context is the clearest expression of our unique biology. Therefore, he argued, we should not see nature and nurture as a competition.

Professor Reicher proceeded to share his fascination with human collective behaviour including how we behave in emergencies and the incorrect notion of crowds as inherently negative. In this Q&A, he details what first sparked his interest in crowd behaviour and his experiences from the Bristol riots in 1980 through to the Covid-19 pandemic. He touches on the importance of leaders and the implications of his research for society.

What first sparked your interest in crowd behaviour?

I vividly remember in my first year at Bristol University studying psychology and learning about theories of group behaviour. Most theories of group behaviour tell you that groups are bad for you as they make you morally and intellectually worse and irrational.

I had expected to go to university to sit around and have deep intellectual conversations. But I hadn’t really found this until I became involved in student politics and we had an occupation of the Senate House. I went along and what I discovered was remarkable to me. People were deeply concerned about women’s access and gender equality. We had discussions around the nature of equality and tactics. I found it intellectually exhilarating.

Despite being told in my studies that groups were bad for you, I had found in this collective movement an intellectual fervent and richness that I’d never found before. In the middle of the occupation, we went to a meeting where the Vice Chancellor was talking and he was belittling us and using this classic crowd psychology, saying that we were irrational, emotional and didn’t know what we were doing.

It struck me that the psychology did not make sense of my experience. The psychology seemed more like ideology that sought to discredit rather than explain collective action. From that moment on, I was hooked!

Can you tell us about your experience in the Bristol riots in 1980? How did this impact your research journey?

I started my PhD and began some experimental work on the social influence processes that I thought were going on in crowds. While I was doing my PhD, the St Paul’s riot happened in Bristol. This was just down the round from where I lived, so I went to St Paul’s and there were lots of police there. I told them I was doing a PhD on crowds and they let me in. The fascinating thing was my experience at the time was completely at odds not only with the literature but also with media accounts.

That night, in St. Paul’s, people were initially hesitant but then they were very friendly to me and very open. The atmosphere was bizarre because on the one hand police cars were upside down, the bank was on fire, but it felt very unthreatening. There was a clear pattern to what people were doing and were not doing. The psychology says that in crowds and riots people explode and attack anything. The next day the deadlines reflected that. The psychology and representation once again were at odds with my experience. The media representation of it was more about condemning than understanding.

This experience, together with my earlier experience of the student occupation of Senate House, made me fascinated by crowds.

What are the positive and negative sides to a crowd?

Often what we get wrong when we look at crowds is the level at which we explain things. The traditional argument is that crowds are all about loss – loss of identity, loss of rationality, loss of morality and loss of agency. The pathology lies in the nature of the crowd.

My work argues that the fundamental feature of crowds is not a process of loss, it is a process of transformation. The first psychological transformation is not a loss of identity, but instead a shift from individual to social identity. The nature of behavioural control shifts from individual beliefs and norms, to group level beliefs and norms. We act in terms of the collective values and beliefs of the group.

Some groups have pathological ideologies. For example, racist groups see ethnic minorities as their enemy. Group behaviour can be pathological, but it is more an ideological- or political- rather than a psycho- pathology. This implies that toxicity lies not in the nature of crowd psychology in general, but in the belief systems of specific crowds. What is more, when you talk about a political pathology, often it involves toxic leadership.

So the issue isn’t so much about whether there are good and bad crowds – there are examples of both. It is more about the level on which you explain what makes crowds good or bad. I argue that it lies in the content of the social identities of specific crowds.

But, in crowds, the shift from individual to collective values and beliefs – what I call ‘the cognitive shift’ is not the only transformation that takes place. There is also a relational shift. In the group, you have a shift towards intimacy because others cease to be psychologically ‘other’ and they become part of your extended social self. They become a parted you. So you become closer to others. You become more willing to cooperate with others and become more trusting of others. All the things that allow you to work together more effectively.

We did one study about disgust. It was a very simple study where we got people to sniff smelly t-shirts. The manipulation was whether the t-shirt had the logo of your university or a rival university. When it had the logo of their own university, participants didn’t particularly like it but they were not too bothered by it. We had people rating their facial expression, they didn’t look quite as disgusted, they smelled it for slightly longer, and they took slightly less time washing their hands afterwards. In comparison, when the smelly t-shirt had the logo of a rival university, their faces contorted with disgust, they sniffed as briefly as possible and rushed over and used lots of soap to wash their hands.

Why this is significant is that disgust is the socially ordering emotion. I can sit in a room with someone I hate, but not with someone who revolts me. The loss of disgust in a group enables them to pull together. In a group you will align the way you see the world, but you are also able to align your efforts to work together to be more effective. You are empowered in groups.

The thing about groups and crowds is you get remarkable solidarity in crowds. People will sacrifice themselves for others because they share the same social identity. You get empowerment and so groups are more effective at changing the world. One of my favourite quotations is by a French historian, Georges Lefebvre, writing in the 1950’s about the French Revolution and he said: “Perhaps it is only in the crowd that people forget their petty day-to-day concerns and become the subjects of history.”

We live in a world made by others, we adapt to rules of others. In the crowd, we make history. We have agency. The whole notion that crowds are bad, because people act like sheep and lose agency, is precisely the opposite of what is true. You have collective agency and can make the world on your own terms. You can translate the briefs and priorities of your social identity into lived reality. What that means in practice once again depends upon the ideas associated with the specific group identity. But the key point is that crowds and collectives are the one way that the powerless can change the world. Martin Luther King said they are the voice of the powerless.

The reason why crowds are feared and pathologised is that, for those who control the world, crowds are a threat to their control. That’s why they disregard them. Both in terms of what crowds do, their empowerment and sense of agency, whether those are good or bad, depends very much on the content of the ideology and particular vision of the world.

In 1934, when the Nazis came to power, they put out a little booklet that went to all schools called ‘The ABC of National Socialism’. They wrote that the first commandment of National Socialism is ‘love thy ethnic comrade as thyself.’ We studied the one place under Nazi control during the second world war where no Jews were deported, the lands of old Bulgaria. Twice the Nazis tried to deport people and twice people mobilised to stop them. We studied the documents that were used to mobilise people to stop the deportation. One of the core arguments is that they don’t use the word Jew, they say these people are a national minority. It is not ‘them’ that are being attacked it is ‘us’ that is being attacked and we have got to love and support them. And so you have the same process, love the in-group, but the social implications are very much dependent on how you draw the boundaries of the categories ‘us’ and ‘them’ and that’s what leads to something being socially good or toxic.

How did the Covid-19 pandemic impact your research?

Well like everybody, the things I was doing I couldn’t do! I became involved in the advisory process at a UK and Scottish level and also as a member of Independent SAGE. We had UKRI funding on group processes during the pandemic and that was with various colleagues. One colleague was in charge of the strand looking at mutual aid. We were doing experimental studies on how shared identity impacted our behaviour and we had a colleague who was doing work on the policing of the pandemic. Like quite a few people, I had the day job, I had the advisory job on top of that and then there was also media work. And so my world became Covid for those 2-3 years.

What were the key things we learned from Covid-19 in terms of the role of behavioural science in society?

The first thing we learned was that it mattered! During the Scottish referendum in 2014, a journalist phoned me and said, ‘can you talk to me about how families argue because one parent is for and the other is against the referendum?’ I ranted at the journalist about why they asked me a question like that when many of the core questions of the referendum are psychological, they are questions about national identity and decision-making under uncertainty.

For me, what the pandemic showed was that psychological issues are relevant not just at the personal or interpersonal levels, they are not just about how individuals act or get on. They are also systemic. They are about fundamental societal issues. I think we began to understand that during the pandemic, as it was obvious that what happened was a function of how people behaved.

I also think we learned something about the nature of psychology. Often we have that image of people, especially people in a crisis, as the problem. People are portrayed as unable to cope with complexity and stress. It is argued that you can’t reason with people as they don’t know their own minds. Those ideas were largely debunked during Covid. Rather, it became much clearer that what was absolutely central had to do with issues of creating a sense of community so people worked together and supported each other. Creating a sense of trust so people would believe you and take what you said seriously. Actually public behaviour was your best resource for dealing with the pandemic.

To me, it showed acutely that we need psychology at a policy and systemic level. But we need a psychology that is less dismissive of people and understands more the importance of social relationships and the nature of communities. We need a social psychology of group processes.

These were the things that were key to me and the failure to address them undermined the Covid response, I think. Moreover, it is critical to recognise that Government has different relationships with different communities. Marginalised groups, ethnic minorities, trust government less, require more support to deal with the pandemic. They were less willing to get vaccinated, less able to self-isolate. Any psychology which foregrounds the importance of social relationships must likewise take inequalities very seriously.

How important are leaders of social groups?

In my early work, I often made the point that groups can work together without leaders, as there is this traditional notion that people become mindless in groups and need someone to tell them what to do. Having said that, leaders are important. They are important to create a sense of group membership; to get people to see themselves as a community and come together; to imagine themselves as being in the same boat. That is partly about what leaders say, but it is also about what they do – their practical policies.

I remember the Chief Medical Officer of British Columbia has this great phrase, “we are all in the same storm, but not necessarily in the same boat.” The important thing is good leadership brings people together because, for instance, it allows everybody to stay at home. We got some way towards that in the UK with the furlough scheme. We could have gone further and there were still huge inequalities, for example poorer people and vulnerable minorities who were less able to self-isolate.

Leadership is also absolutely crucial in terms of shaping our understanding of ourselves, who we are, what we value and how we should behave. Leadership can reflect back to us what we are doing and how we are behaving. A leadership that is constantly telling people off and telling people to stop violating the rules, reflects to us that we are not a community and that other people are doing bad things. A leadership that gives you a sense of the heroic actions that others are taking, how they are taking them and a leadership that supports people to do that, brings people together and also makes the leadership seem to be on your side.

Leadership needs to be understood as a group process of bringing us together, creating a community, reflecting to us who we are. We talk about leadership as ‘social identity management’. We saw examples of that during the pandemic such as in New Zealand with Jacinda Ardern. We also saw bad examples of it where leadership alienated themselves from the population and created a sense of ‘them’ and ‘us’. We also saw Government that set people against each other by making people think of their neighbours as a problem and to keep an eye on them as at any moment they might break the rules.

What are the main implications of your research for society?

One of the problems with some psychology is that it tries to explain human behaviour just at a psychological level. In a sense it tells you, to turn your eyes away from society, because that’s irrelevant, and to instead turn your eyes inwards to the subject. For me, what social psychology should be about is to analyse the ways in which the social impacts on us. Therefore, it should orient you to what it is in society you should look at. What are the critical elements that impact our behaviour? For me, it is very much about how narrative stories and the way the social world is organised creates groups, creates communities, or conversely divides into ‘us’ and ‘them.’

It flows from the argument that the pathology doesn’t lie in our psychology or in the inherent nature of groups, it lies in the ways we draw specific boundaries of ‘us’ and ‘them’ and the ways we explain whether ‘they’ are an asset to us or a threat to us. Insofar as these issues of solidarity, and conversely hatred and conflict, are created by human beings, they are not inevitable and therefore we have it in our hands to change them and we should be accountable for changing them.

Rather than having a pessimistic view that ‘racism is terrible but there’s nothing we can do about it,’ it actually makes us accountable for the world we live in. More specifically, if the way we understand our world and draw boundaries of ‘us’ and ‘them’ is impacted by the leaders, if we are looking at racism, the leaders have to be accountable. For me, things like hatred don’t just happen, they are mobilised. They are not just an inevitable function of our human nature and psychology, they are a result of human activity and someone has created those divisions for particular reasons.

Often we think of psychology as how people perceive the world and how those perceptions impact behaviour. For me, we need to look at much of behaviour as a function of mobilisation and how that comes from the ways we create that sense of ‘us’ and ‘them.’

How can we change an existing sense of ‘us’ and ‘them’ in a particular community?

In understanding the processes that leads to those things, we do begin to make people accountable for what they are doing. It is quite interesting how people often misuse psychology to avoid accountability. One of the classic examples is during the Balkan war, there was a narrative that said ‘this is inevitable as there are ancient hatreds that people are bound to do this.’

Clinton read Robert Kaplan’s book ‘Balkan Ghosts’ that argued this and came to the conclusion there is no point the Americans doing anything or trying to intervene in any way. I think that is profoundly dangerous, because of course there was history. But that history was having to be actively invoked in order to explain to people the position they were in to set up groups they had been living with peaceably for years as their enemies - and generate hatred.

Understanding how people make active choices in the process of creating enemy hood and antagonism is the first step in holding them accountable. It is not that we as psychologists can change the problems of the world on our own, but I think at least we can avoid or challenge misexplanations that may be fatalistic and lead to people just putting up with things they shouldn’t put up with.

What’s the next piece of the puzzle your research is going to focus on?

One of the things I am really interested in, is the way crowds and crowd events aren’t just shaped by social identities but in turn shape our identities and our understanding of ourselves and society. For years I have been doing research on the way in which participation in crowds affects people’s sense of identity and their understanding of who others are. But to me the fascinating thing about crowds and crowd events is that they are not only seen and observed by those taking part in them, but they are seen by the public at large.

We have been doing work around the events following the death of Queen Elizabeth II and also the coronation of King Charles III. Though the crowds seem big, they represent a tiny proportion of the entire population. However, tens of millions watch them, read about them, discuss them. I am really fascinated by the way they serve as a concrete image to tell us about ourselves.

There is a famous book by Benedict Anderson and he talks about imagined communities. He makes the point that a nation is far too big for everyone to assemble and so we have to imagine the nation, it is an imaginary construct. In a way, crowds are the imagined community made manifest. We see Britishness in those crowds. The ways in which those crowds are choreographed and the ways in which those events are structured, the ways they are used to tell us what it means to be British, is absolutely fascinating.

Part of the work I’ve done on crowds has always been to say that crowds were treated as the exception. They were treated as an eruption of the primitive in modern society. For me, crowds theoretically allow us to understand the processes whereby society impacts on the psychology of the individual. But, in practical terms as well, crowds are central in shaping the identities by which our society is organised and we live our everyday lives. The interesting thing is other disciplines, such as anthropology, are aware of that. They think ritual creates identity, but they are so convinced of it, they never actually study it. They look at the ritual and presuppose that they way it is organised impacts how society is organised.

And so, you have this odd situation that psychology doesn’t look at things like ritual, anthropology does but takes them as a disciplinary assumption. There is very little research on these collective events. These large-scale, ritualised performance, such as commemorations and celebrations, and the processes through which they create our identities and social relations in our society.

I continue to be fascinated by crowds. One thing people say is that crowds are very bad for you, in every way, including your health. There is a discipline called Mass Gatherings Medicine, which is about the fact that people feared crowds as the place where the next pandemic would come from. After SARS, people were worried that the Hajj, the annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, would result in people coming together from over 150 nations and sharing their germs. There is that threat. However, some of our work shows that actual participation in crowds creates a sense of community, which endures beyond the crowd when people go home. Fellow members feel that they have a shared identity and have support from one another. That process of shared identity and perception of support, lowers stress and impacts health positively.

We have data from big Hindu crowds in India that shows people do get bugs but overall, health improved. Therefore, the crowd is a public health intervention. When people talk about social prescribing, crowds can be good for your wellbeing because they connect you to others. They raise that wider question of how we create a sense of community that is good for people at every level including in health terms. I think there is something fascinating about crowd participation and the creation of a sense of community and also health.

Importantly, though, it is isn’t just crowds that impact health, it is participation in all kinds of groups. For instance, it was discovered that people in old age homes weren’t drinking enough water so they become dehydrated and cognitively confused. And so they formed these drinking clubs for people to get together and drink water. Then some colleagues asked the question, is it the water or is it the club? They did a study comparing drinking, no-drinking, club, no club and they discovered it was the club that was doing the good thing. Just getting people together to participate together is immensely good for your wellbeing.

This happens at all different levels, it can be a drinking club, it can be a congregation, it can be a crowd. Creating that sense of ‘us’ as a shared identity and connection to others is a profoundly important health intervention. It has been called ‘the social cure’.

About Professor Stephen Reicher

Stephen Reicher is a social psychologist who has been studying various aspects of group process (crowd behaviour, intergroup relations, obedience, leadership, toxic behaviour) for over 40 years He most recently researched group behaviour in the Covid pandemic, serving on the advisory groups to the UK Government (SPI-B) and Scottish Government and as a member of Independent SAGE. Stephen is currently Wardlaw Professor of Psychology at the University of St. Andrews, a Fellow of the British Academy, of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.