Keeping your behaviours in check

Scientists identify the physical connection through which the prefrontal cortex inhibits instinctive behaviours.

From fighting the urge to hit someone to resisting the temptation to run off stage instead of giving that public speech, we are often confronted with situations where we have to curb our instincts. Scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory have traced exactly which neuronal projections prevent social animals like us from acting out such impulses. The study, published online in Nature Neuroscience, could have implications for schizophrenia and mood disorders like depression.

Cornelius Gross, who led the work at EMBL teamed up with Tiago Branco, who was working at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology but is now a group leader at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour.

Tiago Branco said, “These results are very exciting, because they reveal a mechanism that the brain uses to control instincts, which is something that we all need to do in social situations”

The driver of our instincts is the brainstem – the region at the very base of your brain, just above the spinal cord. Scientists have known for some time that another brain region, the prefrontal cortex, plays a role in keeping those instincts in check. But exactly how the prefrontal cortex puts a break on the brainstem has remained unclear.

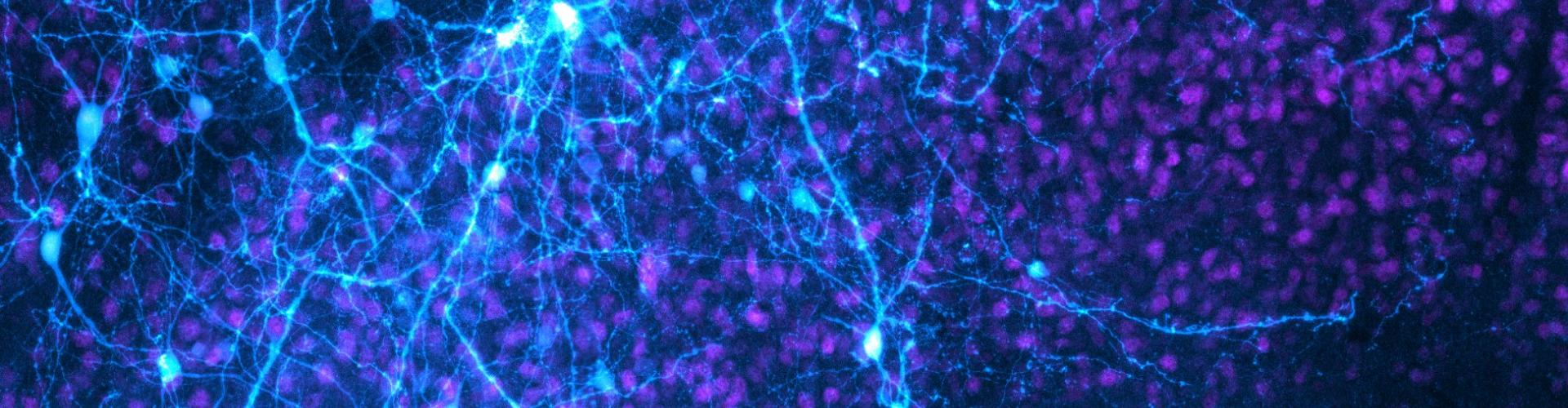

Now, Gross and colleagues have literally found the connection between prefrontal cortex and brainstem. The team of scientists traced connections between neurons in a mouse brain and discovered that the only prominent inputs into the brainstem were from the prefrontal cortex.

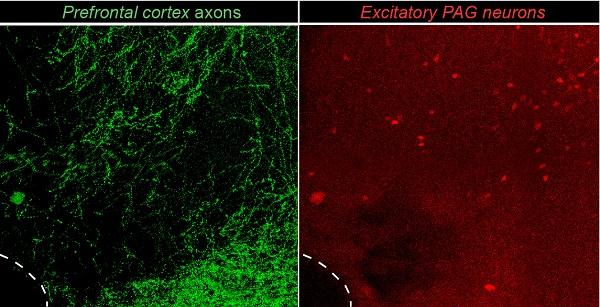

The figure shows section through the PAG, the area that controls instinctive behaviours - the PAG neurons are in red and the axons coming from the prefrontal cortex that inhibits PAG activity are in green.

The scientists went on to confirm that this physical connection was the brake that inhibits instinctive behaviour. They found that in mice that have been repeatedly defeated by another mouse – the murine equivalent to being bullied – this connection weakens, and the mice act more scared. The scientists found that they could elicit those same fearful behaviours in mice that had never been bullied, simply by using drugs to block the connection between prefrontal cortex and brainstem.

These findings provide an anatomical explanation for why it’s much easier to stop yourself from hitting someone than it is to stop yourself from feeling aggressive. The scientists found that the connection from the prefrontal cortex is to a very specific region of the brainstem, called the PAG, which is responsible for the acting out of our instincts. However, it doesn’t affect the hypothalamus, the region that controls feelings and emotions. So the prefrontal cortex keeps behaviour in check, but doesn’t affect the underlying instinctive feeling: it stops you from running off-stage, but doesn’t abate the butterflies in your stomach.

The work has implications for schizophrenia and mood disorders such as depression, which have been linked to problems with prefrontal cortex function and maturation.

Branco added, “You shouldn’t start a fight every time you have an impulse to do so, and it seems that the pre-frontal cortex has the ability to directly inhibit some of the neural circuits that control instinctive behaviours”.