From value to movement: Scientists uncover the circuit mechanism linking decisions to actions

We make thousands of decisions every day, often starting with whether to hit snooze on the alarm. There’s no right or wrong answer. A few minutes of extra sleep offers the immediate rewards of comfort, while getting up brings the longer-term benefits of being on time. Even in this tiny moment, the decision unfolds in stages; we assess the options, assign subjective value to each, and then act on the winner, whether that means getting out of bed, hitting snooze, or turning off the alarm altogether.

But how does the brain make these choices, and how does it turn them into actions? A new preprint from the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre (SWC), shows that the anterior lateral motor cortex (ALM), a region previously linked mainly to movement, also represents the value of competing options before converting a choice into action. The study, led by Dr Oliver Gauld, Dr Chaofei Bao and Dr Ann Duan, bridges a major gap in our understanding of how abstract, value-based decisions are computed and then transformed into physical behavioural enactment.

“Abstract value preference guides our everyday actions, but how does that work? To find a circuit mechanism that transforms such abstract representations to specific action planning is challenging but very exciting,” says Dr Ann Duan, Group Leader at SWC.

Value-based decisions lie at the core of survival: deciding what to eat, when to explore, whether a reward is worth a cost, or which action leads to the best long-term outcome. By studying how the brain computes and compares values, researchers can uncover the algorithms that guide behaviour, revealing fundamental principles behind every choice we make.

Separating decision from action

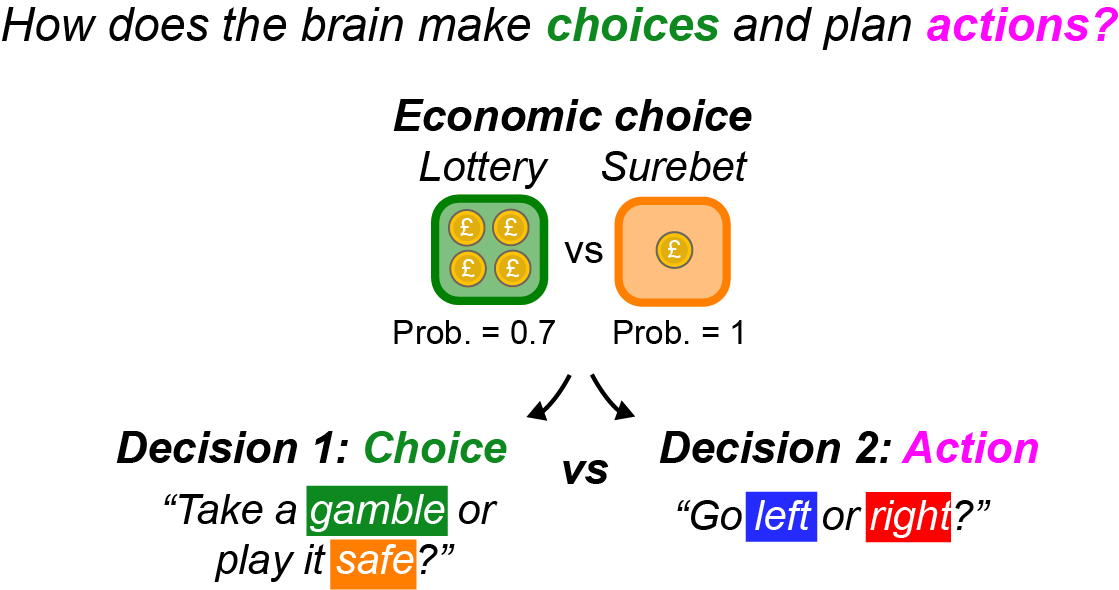

Most previous research on economic decision-making, meaning choices that are guided by subjective value preferences, has focused on humans and non-human primates. It has been assumed that studying such abstract decisions is too challenging in rodents. However, the team carefully designed a task for mice that proved otherwise. The concept of the task aligns with primate studies of economic decision-making.

Not only can rodents perform the task, but it also separates the moment of value judgment from the moment of action planning. This design makes it possible to analyse each stage of the decision process.

The task involves animals choosing between two reward offers: a guaranteed ‘surebet’ or a probabilistic ‘lottery’. A sound cue indicates the value of the lottery choice on each trial. Following the sound, the location of the lottery choice is marked by an airpuff to the left or right.

“Differentiating a value judgment from a movement plan is a big challenge that a lot of studies have faced. We now have a task that temporally dissociates the economic, value-based decision from the later stages of movement planning and execution,” says Dr Oliver Gauld, Research Fellow at SWC who was awarded a Wellcome fellowship to pursue this research. “This study is the first of its kind. We hope our findings will inspire more groups to start thinking about applying circuit tools to understand economic decision-making”.

Diagram representing the choices that need to be made in the task - an economic choice followed by a choice between two actions.

Locating regions

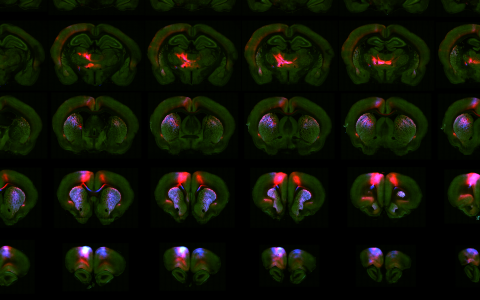

To identify which brain regions were involved in economic decisions, Dr Gauld first used widefield calcium imaging to monitor activity across the entire dorsal cortex while the animal performed the task. “We wanted to use an unbiased approach”, explains Dr Gauld. This showed widespread, state-dependent signals related to both economic choices and actions throughout the dorsal cortex.

The team then used optogenetic methods to systematically silence 17 different regions. During the value-guided decision part of the task, the largest and most consistent effects came from silencing the ALM. This indicates that this frontal motor region is essential when the animal is making its choice between the two options. Consistent with previous studies, inactivating the ALM also impacted behaviour during the movement planning phase of the task.

“One of the things that we were excited about was that the ALM has been extensively studied previously, but mostly in the context of motor planning. This is the first report of any rodent brain region that is causal for abstract economic decisions, independent from sensorimotor contingencies. It was surprising to see it in both roles during the task,” said Dr Ann Duan, Group Leader at SWC.

Cellular resolution representation

Dr. Chaofei Bao then used Neuropixel probes to record from large populations of neurons in the ALM during decision-making. Within the ALM, they found that some neurons encoded the abstract choice, some encoded the upcoming spatial decision. A subset of neurons non-linearly combined the abstract choice information with the spatial planning information.

“A small population of neurons integrated everything that the animal needs to know to do the task well. This conjunctive coding is really strong evidence that the ALM is a critical region for value-guided decisions and actions,” said Dr Duan.

Interactions between two brain hemispheres

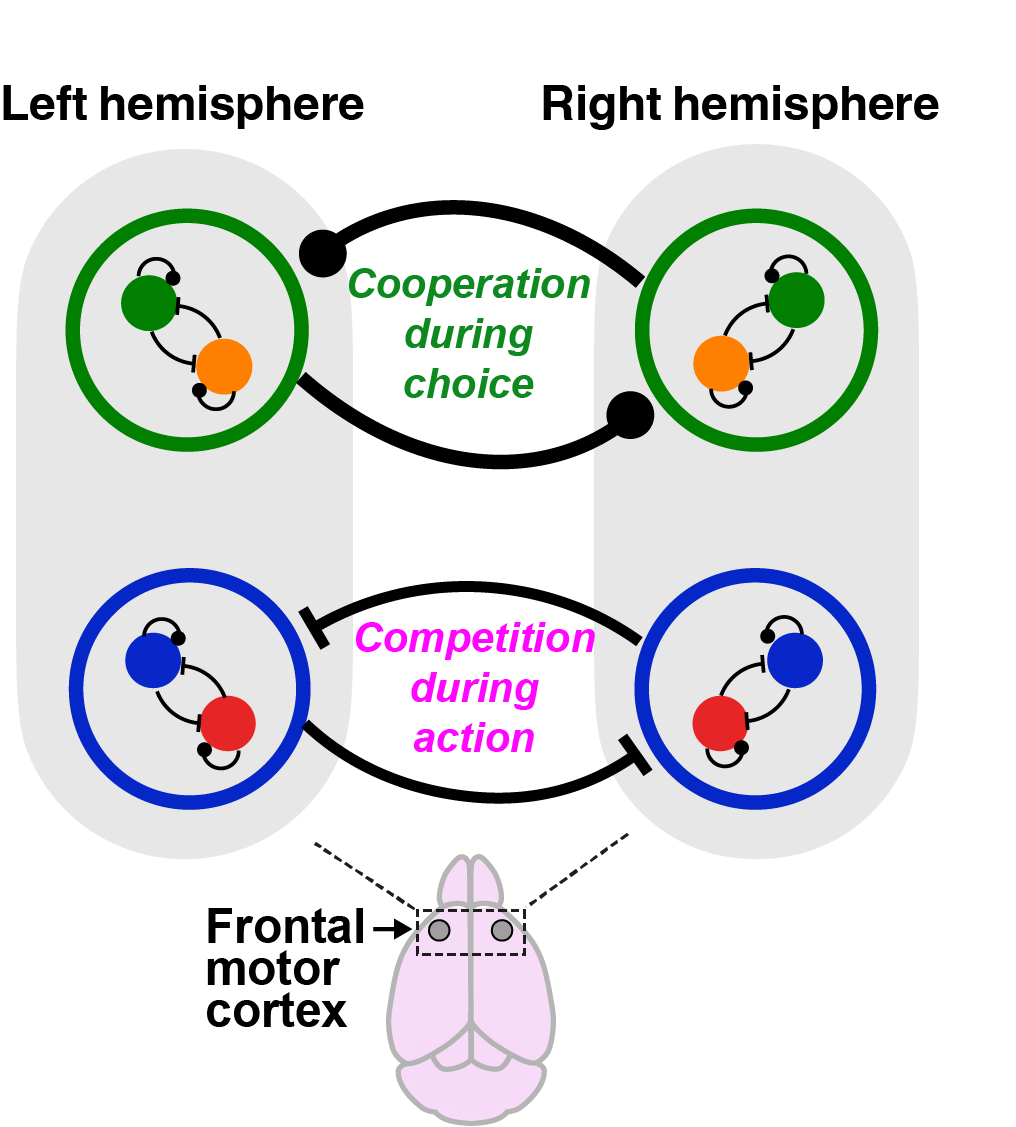

To understand the spatial and non-spatial nature of the ALM’s contribution to the task, the team then silenced the ALM in one brain hemisphere at a time, at each stage of the decision. When they silenced one hemisphere during the early, abstract decision stage, the animals’ performance dropped, but their choices didn’t shift left or right. However, when they silenced a hemisphere during the later movement-planning stage, the animals developed a strong directional bias, choosing the side controlled by the intact hemisphere.

This revealed a clear transition: early decisions may be distributed across both hemispheres, while later movement plans become spatial and lateralised.

To explain this shift, the team built a computational model in collaboration with Drs Jeffrey Erlich, Claudia Clopath, Gauthier Boeshertz and Jingjie Li. This suggested that neurons which represent the value choice in the two hemispheres cooperate, and neurons tuned to the action planning exist in a competitive, winner-takes-all mode – the animal either goes left or right.

Dr. Chaofei Bao then conducted neuropixel recordings from both hemispheres simultaneously, and found exactly what the model predicted: strongly coupled activity during abstract decisions, and then a move to anticorrelated, competing activity patterns during movement planning. This provided strong evidence for a dynamic circuit switch that links decision-making to action preparation.

Diagram to represent cooperation then competition between brain hemispheres.

Next steps

The team are now following up with studies of sub-populations of cells in the ALM, based on their genetic markers and projection targets. They are also looking at deeper brain areas and the dynamics of dopamine as the animals learn the task.

The researchers hope that the principles of this study can also be applied to study other types of decisions, too, such as rule-based decisions and perceptual decisions.

“With this novel paradigm to study how a decision turns into actions, now we can be brave and push this science forward. Our work also has potential implications for understanding what may lead to maladaptive economic choices, with relevance for gambling addictions and impaired financial decisions,” says Dr Duan.