Decoding emotion

Daniel Salzman is known for his research on how the brain represents emotions, values, and internal states. He trained with Bill Newsome at Stanford, where he made influential discoveries showing how activity in neurons in visual cortex modulates perceptual decisions. This early work became foundational in the field of decision-making neuroscience.

As a professor at Columbia University, Salzman went on to transform our understanding of the amygdala. His lab demonstrated that amygdala neurons encode the positive or negative value of sensory stimuli, how expectation modulates their response, and how representations rapidly adjust during emotional learning. By combining electrophysiology, behavioural learning tasks, and computational approaches, his work has revealed that emotional processing involves rich, dynamic representations that interact with cognition, attention and decision-making.

Professor Salzman recently spoke at SWC, and in this Q&A, he gives an introduction to some of his recent research in the basolateral amygdala (BLA). His findings show that the brain can extract multiple, independent emotional signals from ensembles of neurons that individually respond to many different variables.

You've spent a lot of your career trying to understand what emotions are in the brain. How do you define emotion?

In some ways, I lean on my philosophical training as an undergraduate student and try to use terms that describe emotions in ways that they're used in everyday language.

A given emotional term has many facets to it. In everyday language, we can use the word angry and it can actually describe not necessarily one single thing because there are a lot of flavours of anger. But they all get lumped together, and we know the rules of using those words.

Now, if you just approach the study of emotion in the research laboratory without realizing the many facets of any given word describing emotions, you rapidly wind up with a daunting challenge. There is no good way to study all those facets in the laboratory at once. But you can take advantage of the fact that in the laboratory, you can control variables and you can measure them precisely. So my approach, going all the way back to my earliest work as a student, is to define the meaning of not just emotions, but any mental process being studied, in terms of some observable behaviour that we can measure.

In many ways, it's a reductionistic approach, and it doesn’t capture all aspects of any emotion or mental process. But in order to get traction in the laboratory, I think that's what we need to do.

It is worth emphasising that it is an approach that is not completely inconsistent with how we use everyday language because we often ascribe emotions to individuals based on our observation of their behaviour.

Now the question is, when we define an emotion according to an observable behaviour, is that the same thing as an emotion? I'll leave that to the philosophers to debate.

What behaviours do you look at in this way?

By far the most commonly studied aspect of emotion, in my opinion, is emotional valence, that is, its positive and negative quality.

Scientists routinely use observable behaviour for ascribing positive and negative emotional states. For a positive emotion, the behaviour would typically be an approach or a decision to acquire something. Or, conceivably, a whole set of actions that one takes in preparation for doing that. And negative valence typically would be some kind of defensive behaviour or an avoidance behaviour.

A lot of progress has been made studying emotional valence, but of course, emotions are described by many more variables than just valence.

Often, I would say scientists and neuroscientists, especially when studying animals, haven't necessarily had good measures of many of those other variables. There's a lot of room to study emotion at a richer level. Deciding exactly how to do it is a non-trivial problem. Valence is more straightforward, I think.

Can you describe your recent findings on emotional states in basolateral amygdala (BLA)?

In our recent work, mice were exposed to aversive and neutral cues. Aversive cues triggered two distinct defensive behaviours: trembling (which we use to ascribe fear), and entry into a virtual burrow (akin to fleeing to safety).

When the BLA was inactivated, mice still performed these behaviours, but no longer distinguished aversive from neutral cues, showing us that the BLA does not generate movement commands; instead, the data lend support to the importance of BLA in signalling valence, as diminishing BLA activity decreases differential responses to stimuli of different valences.

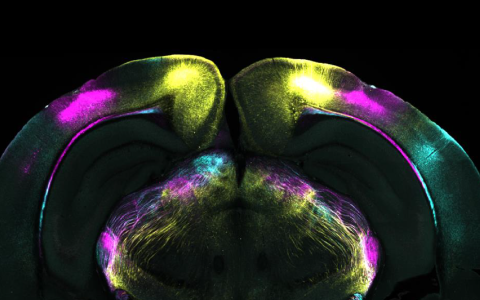

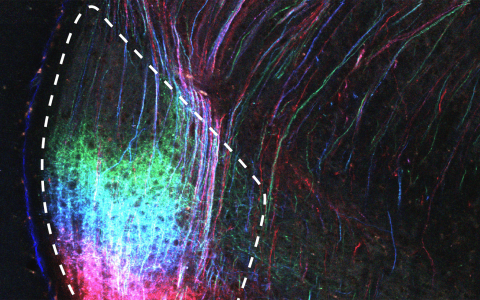

The notion that BLA encodes valence is not particularly new – we showed this to be the case around 20 years ago, as have many other labs. The surprising result came when we used two-photon imaging to monitor neural activity. We found that individual BLA neurons responded to a mixture of stimulus identity, stimulus valence, whether the mouse was in the tremble (fear) state, and whether it had retreated to the burrow to feel safe.

Despite all the heterogeneity at the single cell level, when we examined the population activity space - the pattern of activity across all recorded neurons simultaneously – we discovered that valence, tremble, and safety occupy lower-dimensional structures. This makes it possible to generalise the emotional meaning described by those variables across different conditions.

Further, we also found that the neural population encodes valence and tremble in perpendicular directions in activity space. A readout neuron for one variable can extract it without interference from the other, allowing the same set of neurons to support multiple emotional signals at once. This is advantageous, because you can independently track your fear state (tremble) and whether or not you are in a threatening situation (valence).

Were you surprised by this mixed selectivity?

I think some people might find the degree of mixed selectivity surprising.

But my view is that usually when people have gone in and looked at something, they haven't looked at enough parameters. If you measure or manipulate enough variables, you often see mixed selectivity.

I will say that prevalent mixed selectivity makes it challenging to think about how to study neural circuits. If a neuron has mixed selectivity, then two different variables can be manipulated and potentially give you the level of activity. Reading out the value of a single variable becomes impossible if you only look at the activity of that neuron.

This is why you now start talking about a pattern of activity across an ensemble, so that if you take into account that neuron's activity along with other neurons' activity. In this way, you can sort out the value of one or more variables.

The challenge comes because you still have to map individual neurons into anatomical circuits. The way that people classically have thought about these circuits is with specialised selectivity for one variable, so that anytime you're reading out the action potentials from a neuron, you know what it means. Neurons in a circuit have one job – represent a variable – and the circuit has one job - use the value of the variable to drive some response.

Mixed selectivity neurons don’t fit into that simple view of neural circuits. However, it is known that individual neurons project to more than one neuron and sometimes also to more than one area of the brain. So it is possible that a mixed selectivity neuron could contribute to more than one type of computation, and it would therefore participate in more than one circuit.

Is this what is actually happening in the brain? It's one thing to measure the activity and to know that you could be using it to read out the value of the variable. It's another thing to show it being done in the brain at a synaptic target. We really need better methods that would let us measure this in a behaving experimental subject.

What brought you to neuroscience and the study of emotion?

I initially went to medical school thinking I would become a psychiatrist. I got interested in neuroscience during the course for medical students at Stanford, which at Stanford was the same course that PhD students were taking.

I was especially captivated by the lecture on the neural basis of higher cognitive functions. I had been a philosophy major interested in the mind-brain problem. I went and talked to the lecturer afterwards, and asked about getting involved in research.

He directed me to a researcher who was just arriving at Stanford as a new junior faculty hire - Bill Newsome. Initially, it was just on a one-year gig, a pause for medical school that I would spend in his lab. But then it turned into a PhD, and I converted to an MD-PhD student. I studied the neural mechanisms underlying perceptual decision-making.

In the end, I still graduated medical school, and fulfilled the dream of becoming a psychiatrist by completing post-graduate residency training in that specialty. But I circled back to science right after residency. When I came back to the lab, I decided to study problems that I thought were more related to psychiatry. The first experiments in my lab investigated the amygdala in non-human primates. And everything kind of spawned from there.

Initially, we were interested in how variables that describe emotional states were represented in a primate brain. This interest grew to study how emotional processes influence cognitive ones.

Then we were also interested in how cognitive processes might regulate emotional ones - this is how we got interested in the cognitive process of abstraction, because if you think about how we regulate our emotions, it is often by having a conceptual understanding of situations. The question is, how do you form those concepts in the brain?

In the course of that, we moved into studying mice, and we’ve gotten into many other aspects that are related to emotion and motivation, really trying to take advantage of some of the strengths of working in mice where we can use genetic manipulation and other tools to get to the cellular details of neural circuits.

How does your work in non-human primates and mice relate to humans?

Our work in humans is a direct extension of some of the work in non-human primates.

Our first collaborative paper in humans was published last year in Nature, and it was done in patients who had implanted electrodes.

The patients were performing the exact same task that monkeys had performed in a paper published in Cell four years earlier. And we were able to replicate some of the key features of the data.

But there were some things that we were able to do in humans that we couldn't do in monkeys. This is because humans, like monkeys earlier, were asked to perform a task where you had to learn to use a latent variable. This variable doesn’t have an explicit cue telling you its value – it is actually a context defined by the temporal statistics of events. But if you know that variable, it allows you to use inference to make correct choices in the task more rapidly when contexts switch.

In the experiments in humans, some people would not realise that there was a hidden variable in the task, so they would not use inference when contexts changed. But the cool thing is that in humans you can stop the experiment, and then you can tell the subjects about the hidden rule. Then, of course, all of a sudden then they'd start showing inference. Because you're recording from the brain the entire time, you can look at the difference in the brain pre- and post-verbal instruction.

What we found was an instantaneous change in the representational geometry – the pattern of activity across the recorded neuronal population - so that information about that latent variable was all of a sudden represented in a way that would help support the inference behaviour.

That information was represented in the same way in monkeys, too – though of course not related to a verbal instruction. Monkeys could have learned the hidden rule over the course of training.

Where do you see the biggest progress happening in neuroscience in the next 10 years?

In many ways, I think in the last 10 to 15 years especially, neuroscience has been transformed by two things. One of which is advances in neurotechnology, allowing you to assess the activity of neurons more extensively and in more precise ways.

The other is the emergence of theoretical and computational neuroscience in terms of understanding these very complex data sets that one can now acquire. If you look at most of the influential work that's going on today, it therefore often involves collaboration between theoretical neuroscientists and experimental neuroscientists.

The problem is how to map neural circuits defined at a molecular and anatomical level into this new framework, a framework that is inspired by the work of theoretical neuroscientists.

My guess is that if you look, 15 or 20 years out, there are going to be methods where we can take the tools that are being developed now in theoretical neuroscience for looking at data sets and apply it in a reductionistic manner to neural circuits that one can identify in vivo, and then all of a sudden there would be a bridge between those two things.

That would be transformative if we could do that because we would take contemporary ways of thinking about neural computation, but now do it in a way informed by the anatomy of the brain.