Inside the social brain: What mice teach us about learning from others

If you’re in a new city and you don’t know how the subway barriers work, what do you do? Probably quickly copy someone else. But how does the brain choose when and who to copy? Social animals, from humans to mice, must decide when it is useful to learn from others, especially when they are uncertain about the environment.

Dr Dimokratis Karamanlis at the University of Geneva is exploring social decision-making in mice. Using a task in which two mice make visual decisions side-by-side, he has shown that mice reliably copy a partner’s choice when their own visual cues are hard to interpret. Brain-wide analysis of neural activity shows that the medial prefrontal cortex becomes more active during these social decisions and plays a key role in this computation.

As a winner of the SWC Emerging Neuroscientist Seminar Series 2025, Dr Karamanlis recently spoke at the SWC about his research. In this Q&A we discuss his latest findings.

What questions are driving your work at the moment?

My research interests have evolved over the years as I originally started working on the retina to study vision and how single retinal neurons integrate visual inputs over space. But I felt that early vision was not enough to understand behaviour and how the nervous system works in unison. I’ve now moved to a very cognitive level far from the sensory periphery. We ask how mice integrate environmental information and social cues from other mice, particularly in times of uncertainty.

These are behaviours that humans do a lot. You may be in a classroom, and you don't know the answer - it is natural to glance over and check what another person is doing. Or in a dance class, if you cannot see the teacher performing, you copy the movements of the other students.

These are very interesting behaviours, because we gain information very fast. I’m interested in the neural computations behind this.

How important is social decision-making in societies?

Say there are two ways to gather information. One is from exploring the world, which is hard and time-consuming. The other is to copy what someone else is doing. That’s much easier and safer, as you may avoid risks that the other person is taking during exploration. But if everyone copied, at some point, we would reach information collapse because no one would contribute new information to the environment.

So, there are mechanisms in species to keep this balance at play. Some people may be naturally more explorative than others. This is important as otherwise, for example, we would not discover new food sources.

Can you describe the experimental setup that you use to study social decision-making in mice?

We try to replicate uncertain situations, like when you are lost during an exercise in the classroom. We have mice play a game, and they learn that there is a reward to the left or right, indicated by a visual stimulus on a screen.

When the visual stimulus in front of the mouse is clear, the mouse can be certain about its knowledge and which direction to go. When the visual stimulus has low contrast, the mouse is uncertain.

We then put two mice together. They can see each other, and they do the task in parallel. We adjust the contrast on the screens so that there are situations where one mouse might know the correct answer, but the other mouse doesn't.

What have you found? Do the mice copy each other?

Yes. Because they do this repeatedly, when they don't have the answer, they learn to trust the action of the other mouse and copy what it is doing. They still copy even if the other mouse doesn't offer them much information, so there seems to be something innate.

People asked us if it matters that it is another mouse that offers the information in this scenario. So, we built a small robot to emulate the second mouse in the task. We found it does matter – another mouse seems to be easier to attend to than the robot.

What circuits are involved when these decisions are being made?

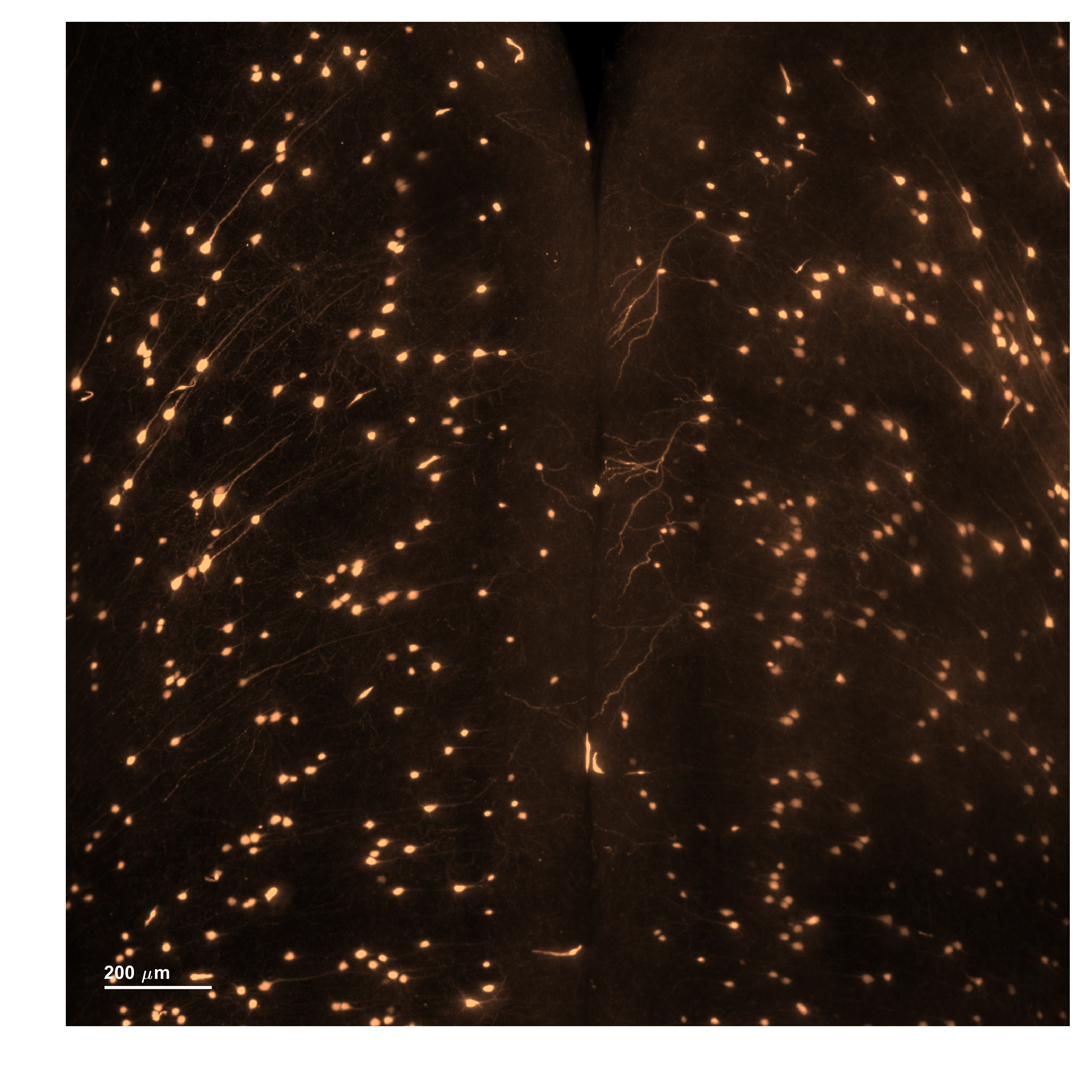

We found that neurons in the prefrontal cortex, including the prelimbic area and the anterior cingulate, have different activity when a mouse does the task alone versus with another animal. These are areas that integrate information from many parts of the brain, and they're heavily involved in decision-making.

Surprisingly, we also found the superior colliculus, which is a subcortical area that is like a small brain in itself, also seems to differ between the two scenarios. This makes sense because the mice have to orient towards their partner, and we know that the superior colliculus does this. And, we know from the literature that these frontal areas and the superior colliculus are well connected with one another.

Maximum intensity projection of an 200-μm-deep imaging volume acquired with a light-sheet microscope. The image contains neurons in the prelimbic area of the mouse frontal cortex that were active during social decision-making.

Did any of your other findings surprise you?

Originally, the project was designed with the idea that mice behave optimally.

This idea has come from experiments done in humans 15 years ago. We expected that if we replicated the scenario, two mice would be better than one. If they are unsure, they can copy. Humans do better with two people.

But actually, when there are two mice together, they perform worse. They tend to over copy.

What does your data tell us about how the brain balances private sensory evidence, the visual stimulus, versus social information? Can you identify neural signals that represent ‘copy’ or ‘go it alone’?

This is something we are still actively exploring. But based on the initial recordings we have, there seem to be neurons that integrate evidence.

When the mouse is in the start position, it looks for the visual stimulus, and this is an active process. These neurons start firing, and their firing rate increases when the stimulus is stronger. When they reach a particular threshold, they stop firing and the mouse starts turning, so it starts deciding.

In some neurons, we’ve seen that firing also increases when the other mouse is moving, and there's no visual cue on the screen. We like to think of them as common integrators of social and visual input. It seems they perform a kind of either/or operation - whatever evidence comes first, they will take it.

Do these mechanisms map onto what we know about human social decision-making?

There is a question about domain specificity. Is social learning something that the brain is optimised for? Or is it just a subset of associative learning? A social agent, let's say, is just another object in the world that you can learn from.

Many people have argued that social learning is domain general - it uses the same mechanism as associative learning.

We find in mice, based on the experiment with the robot, that it also seems to be a general mechanism. You learn from others, whether they are a robot or a mouse, though a mouse is more salient.

How does your work relate to conditions that affect social interactions?

Autistic people may experience differences in social learning, though it is not clear why. Autistic individuals can certainly learn to interpret social signals, but this often requires more deliberate effort. Like the mice eventually learn to copy the robot - responding not because it naturally carries meaning, but because the behaviour becomes rewarding - social cues can be learned from experience.

A potential extension of our project is to try this task with mouse models of autism, and if we observe a deficit in copying, investigate strategies to overcome it.

If you had unlimited funding and no technical constraints, what would your dream experiment be?

Social learning strategies are very broad. We’ve looked at one particular aspect, copying other individuals when you are uncertain about the environment. But there are also other rules, like copying the majority. This is interesting for a society. So if you could have multiple mice and have recordings from all of them, you could investigate how a collective of mice decides something. What are the rules behind that? How does the brain attribute a reward to the actions of different members of the group?

What's the next piece of the puzzle?

For this project, it is to find the single neuron correlates of the integration of the social and visual evidence. We could potentially then trace where the social evidence was computed.

In our task, the other mouse is a visual stimulus, which is read out by the retina. How does this feed into this evidence integration? How does this visual stimulus become an object, another mouse, and then how does that object become meaningful?

Is it through loops of the visual cortex and the superior colliculus? We’d like to explore these questions.

Biography

Dimos is currently a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Sami El-Boustani at the University of Geneva. He originally studied medicine at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and completed his PhD on nonlinear signal processing in the retina with Tim Gollisch at the University Medical Center Göttingen. Dimos uses a combination of computational and experimental approaches to understand visual coding, how sensory signals are integrated into rapid decisions and how these signals are used to guide social learning.