New findings rewrite understanding of short-term memory

If you ask for directions to a new shop before heading out the door, how do you remember them? Do you make a plan of action? For example, I need to turn left, then right. Or, do you remember the instructions themselves – it’s on a corner of the High Street, where the road meets Park Avenue? Each approach places different demands on the brain’s short-term memory systems.

Although the brain has several ways to retain information briefly, most studies suggest we rely on a single strategy. Research in both animals and humans indicates that, in such delayed-response tasks, the brain stores information through movement planning in the frontal cortex - the equivalent of rehearsing ‘turn left, then right’ in our example above.

Psychology, economics and decision science tell us that choosing a good internal representation of a problem can make it easier to solve, yet how the brain implements such choices has remained unclear. Dr Jeffrey Erlich and Dr Jingjie Li at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre (SWC) now show that the rodent brain stores short-term information in the most computationally efficient way, which is not always the frontal-dependent planning route.

“Careful task design shows that we can control which strategy the brain uses – either frontal-dependent movement planning, or sensory working memory - by changing the cost of certain representations,” says Dr Jeffrey Erlich, Group Leader at SWC. “This is a really exciting finding which we hope will drive future research.”

The team also show that animals can shift to a more efficient strategy when the task demand changes.

Now published in a pre-print, their work opens a new line of research into the neural basis of resource rational cognition, linking classic theories of problem representation to computational efficiency. It also highlights the importance of designing complex tasks to understand memory processes.

The locations of working memory

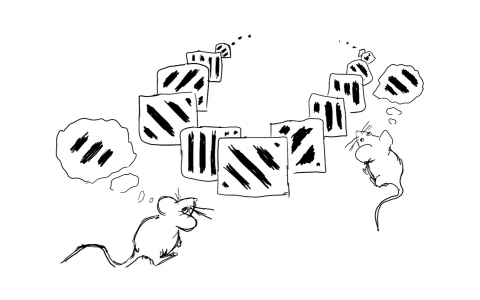

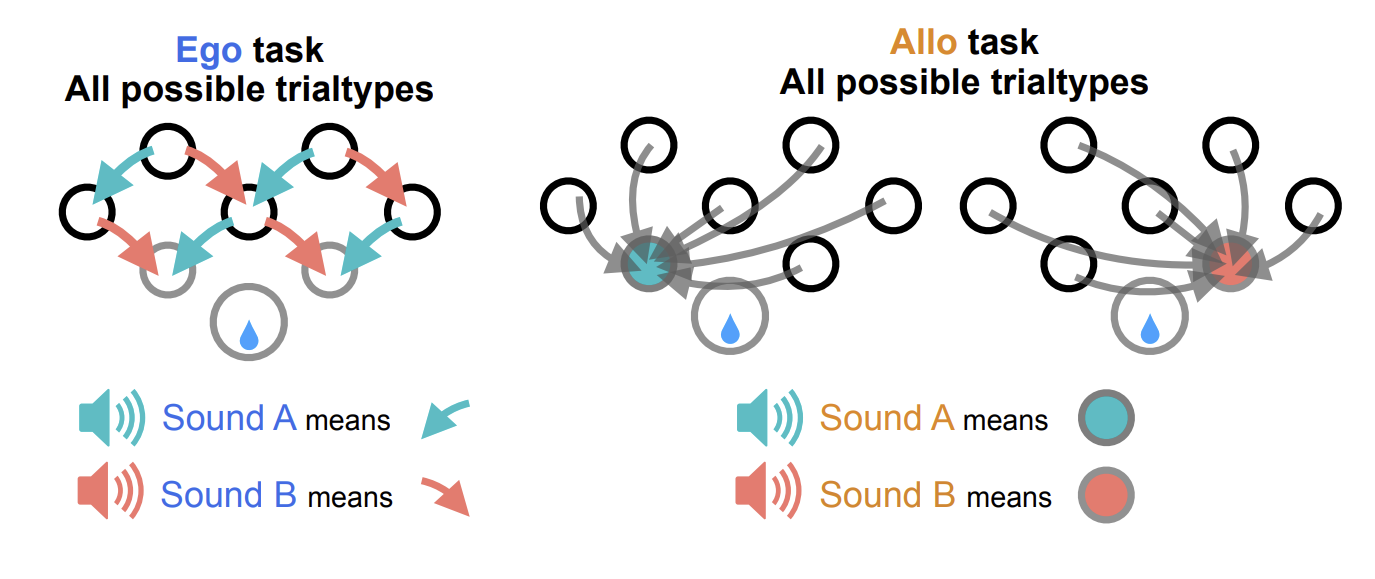

The tasks the team designed required rats to learn to use a poke wall. Animals must choose the correct ports in a task to receive a reward. In the Ego task, after a start port was lit up, one sound cue indicated the correct choice was the port to the left of the starting position, a different sound indicated it was to the right. In the Allo task, after a start port was lit, two different sounds indicated two fixed locations, independent of the starting position.

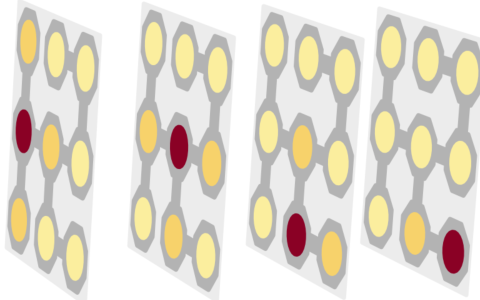

Trial types for each task. The Ego task had 5 different start ports with 8 different start-port × auditory cue combinations. There were only two possible movement vectors in the Ego task: down to the left or right. The Allo task had 7 different start ports with 12 different start-port × auditory cue combinations. Each trial type in the Allo task is associated with a unique movement vector (12 total).

The tasks were designed to encourage the task to be solved in a certain way. In the Ego task, the animal can transform the sound that indicates ‘go left’ or ‘go right’, and remember that plan using frontal cortical circuits. In the Allo task, a movement-based strategy becomes more computationally costly because there are 12 possible directions to get to the correct port. The Allo task is simpler to solve by remembering that the two sounds relate to two specific port locations.

Neural recordings and optogenetic experiments identified that the frontal orienting field (FOF) in frontal cortex was required, as expected, for the Ego task. During the Allo task, however, they found that the rats used the auditory cortex to remember where to go. “This was something we were surprised to see,” said Dr Erlich.

The team also showed that remembering the location, a potential third way of remembering the information, was not used during either task.

Frontal cortex preference

Animals commonly depend on frontal-cortex planning, but some recent studies show that mice can instead use a sensory-based strategy. Why this happens has remained an open question.

“Our data indicate that FOF memory is more robust than sensory-based memory, as the sensory-based representations decayed more rapidly. Movement-based planning also has the advantage of the subsequent action being faster – you are getting ready to go,” explains Dr Erlich. “We know that animals like motor planning, and our results confirm this; it is still the preference.”

Their finding aligns with work in humans, which has shown that items in working memory are prioritised if they have an action associated with them.

Switching strategies and rational cognition

Computational modelling, carried out in collaboration with Dr Albert Albesa-González and Dr Claudia Clopath, predicted that simplifying the Allo task would shift the animal’s strategy from sensory-based memory back to the FOF. This prediction was confirmed experimentally, and rats switched tactics when the task was simplified.

Dr Erlich links the work back to work to ideas on bounded rationality from economist and Nobel Laureate Herbert Simon in the 1950s, who famously said, ‘once a problem is represented correctly, the solution is transparent’.

Bounded rationality is the idea that people make decisions using limited information, limited time and limited cognitive resources. Instead of exhaustively evaluating every option, we use shortcuts, heuristics and simplified models of the world to navigate complexity.

“It’s transformative that this idea of framing a problem in a different way provides an explanation as to why animals may use one strategy over another,” says Dr Erlich, “they are using the most efficient solution to the task. This is a key dimension of human problem solving, and to finally have an animal model that we can start to explore is exciting.”

Dr Erlich stresses the difference between making everyday decisions and those in the laboratory. “In the real world, you may not be using the same areas of the brain that we’ve seen in laboratory tests. Even in experiments with humans, we do a lot of assuming. It is exciting to explore which of the long-held beliefs about neural mechanisms of cognition might be updated if we explore richer behaviour tasks. ”

Next steps

The researchers aim to refine the task to pinpoint when animals switch strategies, allowing them to track a transition from one tactic to another.

They also want to identify the areas and circuits in the brain that are responsible for keeping track of cost and deciding which strategy to use.

Dr Jingjie Li and Dr Jeffrey Erlich